Flax – the Untold Story

By Erik Wilcock

The Early Years 1971 – 1976

It is poetic justice that I’m writing the biography of the Oslo based Rock Band, Flax. When I became the sixth member of the group in early ’73 (non-playing lyricist), it was based on the rumour that I was a bit of a poet. All I can say is that from the moment I put pen to paper for Flax, my career in poetry was finished. Good luck for anyone who read or heard my poems, I guess, but that’s another story.

The name Flax is a corruption of the Norwegian work FLAKS, which means good luck. Its opposite is UFLAKS – bad luck. Learn the words because this is a saga of FLAKS (F), UFLAKS(UF) and a unique band of musicians, who became Flax.

Flax were formed in 1971, a seven piece, which included a horn section. The standard fare was cover material from the likes of Joe Cocker, Mountain and Cactus. But this was the suburban Flax and they needed to move on and move they did, to downtown Oslo. The ambition, however, was to make it big and move uptown – but that came later on.

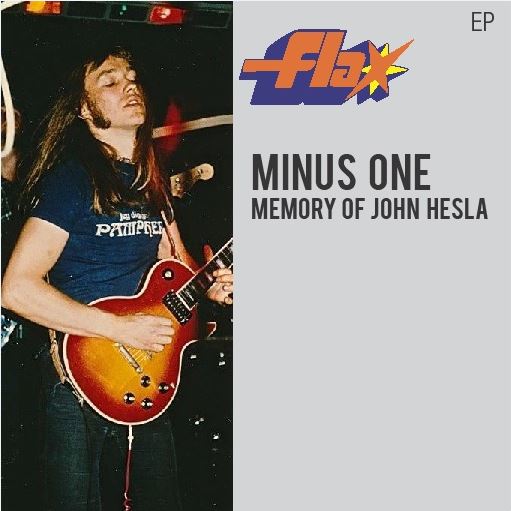

Flax had now slimmed down to a five piece. At the centre of this were Hermod Falch (vocals), John Hesla (lead guitar) and Lars Hesla (keyboards). These three would become the ever-presents of the band and would work with assorted bass players and drummers, some of whom have become legends in their own time. Flax had become a solid unit but they needed to produce original material – in English- and that was where I came in.

At a student town, perched high up in the hills above Oslo, Hermod Falch was combining his music with being an undergraduate student of Psychology. I was doing postgraduate work in Literature and one day a guy by the name of Ulf Elvebeck (Wolf Riverbrook in English – RIP) introduced me to an extraordinary looking Falch. He was sporting a haircut that out-Afroed any Afro, a moustache sculpted by Salvador Dali and black leather jeans that could only be put on with a shoe horn. ‘Can you fix up these lyrics?’ he asked like I was some kind of car mechanic, ‘You see our English is crap and we gotta compete, gotta sing our songs in English. Take a look.’

It was weird stuff: exorcism, black arts, naked nuns: hell on earth. Our meeting could almost have been lifted from a scene in spy movie but the information being passed was not classified, it just needed a little bit of decoding, rejigging and a touch of poetry. I was hooked, so hooked that I rewrote one song from top to bottom and then went away and thought about writing some more. Unfortunately, I would have to continue the writing at a distance: I went back home to England in ’73 having completed my Research work in Oslo. From now on, communication with Flax was by pen, paper, old typewriter and the efficiency of the Mail services in England and Norway. Later, with the advent of the audio cassette the written word would be enhanced by sound.

During this period Flax were graced with the bass playing of Hans Rotmo, a giant in the pantheon of Norwegian Folk Rock Music. They also were getting more gigs and a bit of a reputation of pushing the limits of sacrilege. Hermod Falch had heard about the book the Exorcist and the film that was being adapted from it. It coincided with a lot of National Press stories about exorcisms being carried out in the South West and West of Norway, popularly known as the Bible-Belt. The articles were becoming quite scandalous as they often featured priests and young girls in potentially compromising situations.

Hermod Falch made a decision to run with this topical subject and pre-empt the ‘Exorcist’ film by creating what he termed ‘auditory exorcism’, around which Flax built a stage act. Many thought the concept was a brilliant coup de theatre – except for the elders in the South West and West of Norway, who promptly banned them from appearing there.

The show went something like this: the lights would go down, Gregorian chanting was heard: darkness. Next: a very gradual fading up of the lights as a coffin was borne through the crowd from which Falch would slowly emerge, terrifying those at the front (and half the band), before launching into ‘I’m the demon in your heart!’.

Whether it was faint-heartedness that precipitated Rotmo leaving the band, we’ll never know but his new band Vømmøl would be right up there and kick start his stellar career. His replacement, Arve Sakariassen, would stay with the band for four years and so the core of three became a core of four (five if you include me) and then a coup: they recruited Willy Bendiksen on drums.

Willy was no ordinary drummer or, should I say, is no ordinary drummer. Aged 14, he left home, quit school and dropped everything to be a rock star and he achieved it and part of his journey towards becoming a top international drummer was his stint with Flax, which would include him quitting and re-joining them three times.

Flax were now going places, mainly by road in an old VW with no heating, which is tough in a Norwegian Winter, when it’s usually cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey : ‘UF’, cried the press when they wrote this chilly story. The South Westerners smugly sneered at Flax and regarded it as God’s punishment. But there was little to be sneered at when they performed. The coffin malarkey was ditched because the fans came to see musicians not undertakers. The sound was tight and getting heavy. The rhythm section was really powerful and this allowed the Hesla brothers to experiment more with the new material and Falch to ply his unique vocal take on other unlikely themes: the plight of medieval foot-soldiers in ‘Crusaders’ and the surreal nature of ‘Mirrors’, which was inspired by Cocteau’s ‘Black Orpheus’.

It was time for Flax to up their game and spread their wings. They got a brand new truck to take them on a tour of Germany and it broke down on the Autobahn and disrupted their schedule. ‘More UF for Flax’, railed the papers but as you know, all press is good press and this resulted in lots of F.

Their reputation as a top live band resulted in them being much sought after (lots of F) despite the ban placed on them by the South Western and West God Squad. NRK or Norwegian Radio most obviously have been impressed with what they had discovered about the band, because they gave Flax an hour long programme. Now this might not seem important at first glance, but what you must understand is that there was only one Radio Channel in Norway back then, so the world and his wife tuned in to hear Flax (even people in the South and West) and one of the listeners was big at Polygram records. He promptly offered them a recording contract (huge F). There were hundreds of bands in Oslo at the time but only a couple could boast of having secured a deal with a major recording company to be issued on the Vertigo label.

So, Flax One was conceived, part concept album based on the original dark numbers whose lyrics I had ’ fixed’ or ’ recomposed’, together with the new songs they’d put together based on my new lyrics: the guys were in a good place to go vinyl. Then UF: Willy Bendiksen left the band one month before the recording was about to start. As Falch said at the time, ‘There we stood, naked, record contract in hand but with no Willy.’ The sense of impotence was total and the months spent finding a suitable replacement for Bendiksen both delayed the recording process and kept Flax off the circuit: no gigs, no record, result: total UF.

Finally they found Bruce Carl Rasmussmen an American born Norwegian, with prodigious talent. They duly went into the Scanax studios and recorded their first album for the ludicrous sum of 3000 Norwegian Kroner or £300 or $300 dollars or, if you want be really modern: 250 Euros. A bargain for Polygram records, who would get their money back in spades in the years to come – and that includes today (01 February 2013), because the album is alive and well and still selling.

Post Production Syndrome (PPS) is something that affects performers across the board. I know this having directed well over thirty plays and musicals in youth theatre. When something is done and dusted there can be a terrible sense of emptiness. PPS or UF hit Flax hard, because in the five months between recording the album and it finally hitting the shops, Flax disbanded. Well, not totally, as a non-playing member, they forgot to tell me. But then again, I was living 700 hundred miles away in England still making notes and ideas for new songs. In the meantime, Hermod Falch returned to full time study, the Hesla brothers joined other bands and Bruce Carl Rasmussen headed back across the Atlantic to study 4 years at the Berklee College of Music in Boston, USA.

What of the Album Flax One, then? Its release began as farce. The album was issued without any fanfare or press coverage. Which is odd because Flax were one of the first heavy rock bands from Northern Europe to have succeeded in releasing an LP on an international label. It could have been a field day for the Norwegian Press, as they love to bang on about Norwegians achieving in the big wide world but Flax One passed them by.

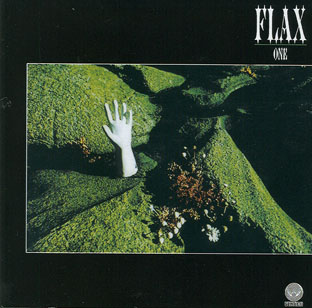

With no band to promote the album and no PR machine at work, it should have been the death knell of the album but it would not lie down and give up. After all, it had guts. Not only did it survive, it thrived. Its cover perhaps offers a clue: a solitary hand rising from the green algae of some aged rock. Was this a nod towards the Arthurian Legend: the hand in the stone, maybe, or merely a surrealistic take on resurrection? Who knows? The simple fact is that this album, kept its heartbeat going. Its popularity grew, which made it hard to come by and soon it would become a collectors’ item.

For fifteen years Flax One was ranked as the most sought after album at Norwegian Rock Album Fairs and it only moved slowly down this chart when someone thought to release it on CD in1999, 2005 and 2008. In October 2010 it was reissued on green and black vinyl. The green version never even made it to the shops due to pre-ordered sales.

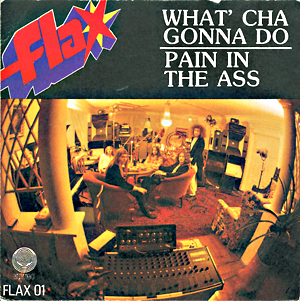

‘A Pain in the Ass’ is the track from the album, which has been recorded the most. Besides appearing on Flax One, it was issued as a single in 1978 and would feature again on the 1980 album ‘Monster Tapes.’ It became a hit and is still a firm favourite with all Flax fans.

If you’re interested, the lyrics ostensibly describe the continuation and ramifications of a relationship, which was a mistake from the start. But it’s not about that at all, though I had had experience of such relationships. I actually wrote most of the text while I was stuck in traffic on the A6 near Manchester . ‘A Pain in the Ass’ is actually about the arduous road journey from Norwich to Manchester, which I had to make many times a year in the 70’s and 80’s.The A6 at Alderley Edge is still a pain in the ass. Ask any Manchester United football star, because that’s where they all live.

Flax Part 2 1978 – 1986

Winter 78: Falch and the Hesla brothers set about resurrecting the band. After all they had charted with a single, folks were beating down the doors to get a copy of Flax One and they had the promise of fresh material from the English bloke who wrote the words.

‘Send more words! Regards Hermod’ was the standard letter. My standard reply, (if I had nothing finished) was to say that I’d got some great ideas, which just needed fine tuning. ‘Dimitrij The Lover Boy’ was a case in point. All I had was a title. ‘An amazing idea!’ wrote Hermod, ‘send it immediately.’ I had no choice but to compose. One week later ‘Dimitrij’ was finished, along with ‘Who Calls the Shots’, ‘City Man’ and ‘Senseless’. All would appear on the second Album ‘Monster Tapes’, issued in 1980.

I must confess that I have no idea what happened once my texts rolled off the pen and landed in Oslo. The creative process that went on is a blank for me. That Flax were now prepared to shed their predilection for topics linked to the dark arts and collaborate with me to create music about the arrogance of Margaret Thatcher’s City Bankers, ask existential questions (Who Calls the Shots) or sing about the physical attributes of a sexy male called Dimitrij was startling. The best bit though, was that I liked what I heard, even though this only happened when I unpacked the parcel containing ‘Monster Tapes’ and applied needle to vinyl. I had no idea what to expect.

By the start of the 80’s Flax were at the top of their game. They had broadened their catalogue completely and, put simply, were very good at what they did: they rocked. They were a highly skilled band and this, together with the new material, allowed them to diversify their music. This also made it hard for the pundits to categorize them. Outwardly they looked like a bunch of hard head-banging metal mongers. But drill down deeper and there was much more.

Except for the odd few months here and there, the magic five of Falch, Hesla J, Hesla L, Bøgeberg and Bendiksen were continuing to produce a unique sound and were gigging regularly. They played all the major rock festivals in Norway. Soon they became the support-band of choice to top international acts whenever they were on tour in Norway: Doctor Hook and The Medicine Show to name but one. Flax enjoyed this role tremendously because they played to big audiences and rubbed shoulders with the great and the good. Another offshoot of being a support band was the chance to tuck into the headliners booze and food packages. Nobody missed what they gorged on because they were either too stoned or too knackered to care. These were good times.

Monster Tapes (1980) received good press and sold well. On the back of this, Flax hit the National TV screens. Once again, they appeared to a captive audience as this was the only channel available at the time. A massive TV audience watched them blast out a superb version of ‘Who Calls the Shots?’ Even those from the South and the West sat up and took notice, despite the fact that the track had an atheistic existential theme.

By now the lyrics by letter had been superseded by lyrics on cassette, with commentary. This meant that I could explain the concepts behind the words or even suggest the motif that I was after. ‘Uptown’, released as a 7” single in 1986 serves as a good example. I drew my ideas from the film American Graffiti, which focused on kids in America who were trying to escape their poverty. They could only afford the old and massively big cars of the 60’s and drove round in them causing mayhem. In my cassette based commentary on the number, I was able to explain that the spare lyrics were meant to replicate the changing of gears on a car: auditory driving. John Hesla’s guitar work on this track echoes this idea brilliantly.

And now we turn to the skeleton in the closet: Flax Live, the unrecorded album. If you had to submit this as a piece of fiction it would be hard to believe. The fact that it is fact makes it even harder to believe.

EMI was keen to capitalize on the success of Flax and decided to invest in the recording of two gigs. Looking at this cynically, a live album was a cheap way of plugging a gap before Flax Tracks (released in 1987) was put together. And besides, they were certain there would be demand for the live sound. I know, because I’ve got a cassette of what would become Flax Tracks recorded in Trondheim. It’s a storming performance and is a different animal from the final LP.

So the roadies, the techno wizards, the venue hosts and the record company set up all the wires, mikes, recording equipment – you name it, they put the stuff in. There was even a mixing desk to record the audience’s reactions. If you stretched the gaffer tape that was used in those two gigs from end to end, it would probably take you from downtown Oslo to the Russian Border.

Everything was set: full houses for both gigs. At Chateau Neuf, Oslo, Willy Bendiksen was cock a hoop and leapt out from behind his drum kit, only to find himself in a pit, five-six feet deep (160-170 cm), dug especially to accommodate the state of the art recording kit. Willy was nearly out on his feet; he was lucky to escape with his life. But showman to the last, he ran round the audience shaking hands, high fiving: the lot. When he finally made it back on stage, he sat down at his drums, composed himself, and proceeded to give one of the performances of his life. It drove the rest of the band to new heights and they looked forward to the next gig. They knew there were a few things that they could do to make things sound even better. Two great live shows would surely make one hell of a great live album. Even a pessimist would agree. But the pessimist should have kept his pessimism: nobody thought to check the leads. Most of the plugs were unplugged. ‘Flax unplugged!’ ran the headline….. UF, UF and ….. UF!

Maybe this accounts for the fallow period that followed, Willy, Jørun and Lars all left for other bands, and then came back. Undoubtedly some momentum was lost during this time. It would, however, be recaptured during the creation of Flax Tracks, the third and final album. But it would not be enough.

The material for the third album pursued them theme of identity. It started with ‘Going Nowhere’. This was an autobiographical number about saying enough is enough – I want to be me – hands off. After that most of the songs came pretty quickly. They weren’t all domestic dramas, though – the D.J.’s Last Waltz, a song about people who put themselves on the line by performing in public became a bit of an anthem at gigs. My memories of it are very strong, because I was at Bel Studios in Oslo for two days when much of the recording was done. It would be the only live collaboration between the band and their non-playing member.

For the first and last time ever, I had the opportunity to rewrite bits that didn’t scan or fit. I also wore my stage director’s hat when it came to the delivery of certain lines in songs. ‘Going Nowhere’ was going nowhere, we tried all sorts of things but it never sounded right. So I suggested that Hermod should more or less speak the opening line of each verse and then just ramp up the anger. He tried it out and looked round at the rest of the band, ‘He’s trying to turn me into Lou Reed!’ he scowled but the others liked Hermod as Lou Reed and it stuck.

Quite a lot of the backing track had been laid down for ‘D.J’s’ by the time I arrived. What was missing was John’s guitar work, particularly the solo. He calmly slipped into gear and produced an astonishing piece of artistry. I was applauding and saying it was mesmerising. John grunted and started again, apparently it wasn’t good enough. The rest is silence.

I left the studio and went back home happy. The Album was originally going to be called ‘Wild Party’ but it didn’t seem fitting, given the subject matter. I offered the compactly rhymed ‘Flax Tracks’ and it got the nod. I had the final privilege of naming the third and, as it turned out, the final album.

As you would expect there would be a large amount of UF surrounding its release. The cutting of the album, undertaken in the Netherlands, was so atrocious that they had to recall it and start again. From recording to the release of Flax Tracks two long years had passed. !987 saw the album re-released but it was all too late: Flax was no longer a performing outfit.

The last tour they did was in 1985. Sid Ringsby (ex TNT, ex TinDrum, ex JORN, ex Ken Hensley (ex Uriah Heep) and Live Fire) had replaced Jørun on bass and the final gig was in Stange, Hamar, about 100 miles North of Oslo. No doubt they played ‘The D.J’s Last Waltz’. No doubt the crowd joined in with the refrain, ‘DJ, DJ,DJ, DJ’s Last Waltz’ (as the lyric went), oblivious to the fact that this was Flax’ last waltz. Did this song foreshadow the end of Flax? Hermod Falch would probably reject this, because he takes the view that Flax never ceased to exist. So long as he and the Hesla brothers are around, then Flax is still alive: it was never formally wound up. And I can verify that by the lyrics written post 1985 that never got any musical accompaniment.

There was talk about reforming in the 90’s. I even penned a track called ‘Back on the Road Again’ just in case. They decided, however, to leave things as they were. The albums and singles would look after themselves: the vinyl would become compact disks and they in turn would be re-mastered and morph into downloadable MP3’s. Yes, you can download ‘A Pain in the Ass’ for 89 English pence, or $1.20, or 1 Euro or 8 Norwegian Kroner. It’s a steal, get one today.

So that’s the story of Flax told from my perspective. I sure the major, minor and occasional players will have their own take on things. I look forward to hearing them.

Erik Wilcock May 8 2013 England.